My thoughts on breathing...

A bit more information as it occurs to me about how breathing impacts your health and well-being. If you have questions or want me to address a particular topic, please don't hesitate to contact me!

How can inspiratory muscle training help with symptoms of reflux? It has to do with the mechanisms behind gastroesophageal reflux disease (or GERD). GERD is caused by the upward movement of gastric contents from the stomach into the esophagus. This happens when the sphincter between the stomach and the esophagus (meant to be a one-way door) loses some of it's strength and function. The result is that stomach contents end up flowing backwards into the esophagus (the pipe that food travels down into the stomach after we swallow). Symptoms of GERD can be:

GERD can be difficult to treat and should include a an approach that includes lifestyle changes (diet, weight loss) and may include medications. But more recent evidence has shown that strengthening the diaphragm can help. A few studies have shown that participants with GERD who performed inspiratory muscle training for 4-8 weeks, had reduced symptoms of GERD. Researchers theorize that IMT helps to improve the function of the lower esophageal sphincter. For the more recent study abstract click here.

0 Comments

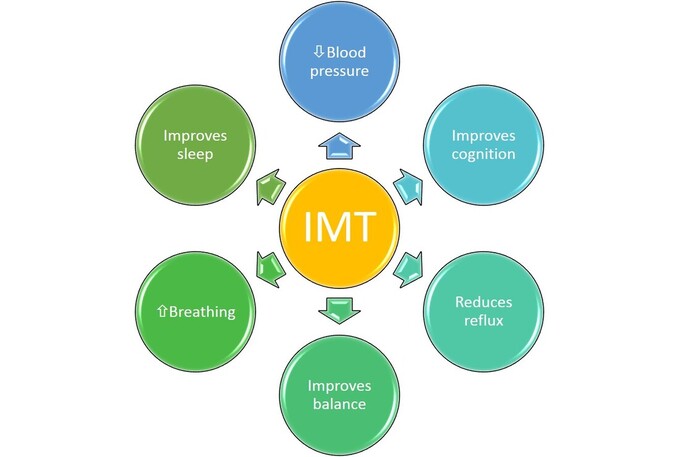

As we continue on with our series on inspiratory muscle training, we are going to talk about how training your breathing muscles can improve your balance. Yes, that's right, I said balance. I know you must be wondering how breathing muscles affect balance, so let's start with a little talk about one of the other functions of the diaphragm: postural control. Back in 2000, researchers discovered that the diaphragm would contract during movements that affected the trunk, that were not related to breathing. This contraction they discovered, increased the pressure within the abdomen and therefore caused increased stiffness (or stability) of the trunk. Since that time, numerous studies have looked at the role of the diaphragm in postural stability and some very interesting results have occurred. One study found that fatiguing the diaphragm changed the way a person responds to balance challenges. Normally, when we are faced with unstable surfaces (standing on soft ground, walking on a suspension bridge), the muscles in our back along the spine will contract to keep us upright and steady. But if you fatigue your breathing muscles, researchers found that the back muscles can't do their job properly and then the muscles in the ankle are used more, which actually leads to less stability (you sway more). This is significant because in some respiratory diseases (and in aging) the respiratory muscles can become weakened. This could impact balance and lead to an increase in falls among those groups. Which leads to the next study, where researchers then looked at the effects of 8 weeks of inspiratory muscle training on a group of otherwise health older adults. The results were surprising. They found that performing IMT for 8 weeks not only improved respiratory muscle function, but it also improved balance! Falls are a major health concern for our older population, so these results are promising. So again, another seemingly far reaching effect of training your breathing muscles. This isn't anything wild and far-fetched though. It's using simple strength training principles on a muscle we previously hadn't really thought of as benefiting from getting stronger. Because the diaphragm has such an influence over a number of systems (respiratory, muscular, gastrointestinal, cardiac) then we can certainly draw some conclusions as to the benefits of having it function as best as it possibly can! Stay tuned as we explore a bit more of the influence on your gut function in our next segment!  There is increasing evidence about the benefits of inspiratory muscle training on overall health. A number of studies have looked at IMT to help with sleep apnea, blood pressure, reflux disease, cardiovascular fitness, cognitive function and balance. A very exciting study to come out of the University of Colorado had participants do 6 weeks of high intensity IMT - a few minutes per day of breathing into an inspiratory muscle trainer. While they were initially looking at the effects of IMT on obstructive sleep apnea, they found that participants had reductions in blood pressure and improvements in cognitive function. This has fuelled a more in-depth project to look at the effects of IMT on blood pressure. You can read more on this study here. Early on in the Covid19 pandemic, Cardiorespiratory Physical Therapy Specialist Rich Severin co-authored a paper looking at the role of respiratory muscle weakness in poor clinical outcomes of respiratory infection. He noted that reduced respiratory muscle strength was common in individuals with poor health and in particular, obesity, and this weakness may lead to increased medical intervention requirements in the wake of respiratory infection. Thea authors suggested that "in patients identified as having respiratory muscle impairments, respiratory muscle training may prove valuable in mitigating the health impact of future pandemics." You can read his study here. There is also an increasing amount of studies looking at the benefits of IMT to help manage gastro-esophageal reflux disease (acid reflux) one of the most common diseases. It seems that improving diaphragm function also improves the function of the sphincter between the stomach and esophagus, thus reducing reflux. Click here for an abstract of a recent study on IMT and reflux. Why are we seeing these benefits of training the respiratory muscles? A lot of it comes down to the function of the diaphragm, which extends beyond just breathing. It has roles in:

Stay tuned for our next blog looking at the effect of IMT on balance!  I think the best place to start our journey into Inspiratory Muscle Training (IMT) is by taking a look at perhaps the most obvious place where training your breathing muscles may have a benefit - lung disease. People with lung disease like asthma, COPD and fibrosis generally have an increased awareness about their breathing. The processes affecting their lung function can make breathing harder for any given activity, which means they are exposed to sensations of breathlessness more frequently. When we perceive (or even anticipate!) the need to breathe harder - like with activity - we may shift breathing patterns to use more secondary muscles (see previous post). This type of pattern is often inefficient and not sustainable for long periods. The secondary muscles are quite greedy - they use lots of energy to work - and can therefore increase the work of breathing (meaning they make breathing feel even harder). When muscles used for breathing start to fatigue, they will trigger something called the metaboreflex, and blood that would normally flow to your muscles in your arms and legs, is redirected to the muscles used for breathing. This is because no matter what you are doing - breathing always wins! So the situation looks like this: you start to feel breathless, so you breathe harder. The harder you breathe, the more energy your breathing muscles need. The more they need, the less energy flows to your leg muscles. Now you not only feel breathless, but your legs feel heavy too and you have to stop doing an activity. This actually happens to everybody eventually once a certain level of effort is reached- in athletes in happens much, much later into activity. But for people with severe lung disease, this can happen just from walking up the stairs. This can then lead to a vicious cycle of inactivity - you fee breathless when you move, so you move less, which makes you more breathless when you do try to move. In an effort to help people with lung disease move more and reduce sensations of breathlessness, research has focused on the effects of strengthening the breathing muscles, in an effort to delay the metaboreflex. And the results are promising. When the respiratory muscles are strengthened, people have reported less breathlessness and improved tolerance to activity (ie they can walk farther). Although IMT make no changes to lung function, it can improve quality of life. IMT is easy to use (takes a few minutes a day to perform) and is cost effective and can be a great add-on to managing lung disease!  Inspiratory muscle training, or IMT, is simply a form of strength training for your breathing muscles that help you breathe in. The main inspiratory (inhale) muscles are the diaphragm and intercostals (rib muscles). These muscles do the lion's share of the work of breathing at rest. When we are more active, secondary muscles are called upon to help increase the volume of the lungs by expanding the ribcage. These muscles are in the neck, chest, shoulders and back - there are lots of helper muscles for breathing when we are active! The muscles we use for breathing are just like any other muscle in the body and can weaken due to illness, injury, aging or disuse. Well, it's not like we intentionally not use our breathing muscles, but sometimes when we rely more on our secondary muscles of breathing (those ones in the neck/chest/shoulders), then it can lead to underuse of the diaphragm. I find that people with asthma, allergies and anxiety tend to use these helper muscles more than their diaphragm. This in turn can lead to premature shortness of breath with activity, and sometimes even unexplained breathlessness at rest. Anyway, just like our other muscles, the breathing muscles can also benefit from strength training. Except for that it is hard to simply lift a weight with your diaphragm. And although general cardiovascular exercise - like walking, running or riding a bike - does improve your breathing, it sometimes isn't specific enough to address the muscle weakness of the breathing muscles. Often, when the muscles are weak, they will limit how much you can push yourself in exercise. So researchers began to look at what happens when you specifically strengthen your breathing muscles. By creating a device that adds resistance when you breathe in, they found that they could specifically target the inspiratory muscles. They also found that this increase in strength produced not just better breathing, but also improvements in a wide variety of things - blood pressure was lowered, sleep was improved, breathlessness was reduced and in some athletes, performance was improved! Over the coming weeks, we will highlight some of the latest research on inspiratory muscle training - maybe you will see how it can benefit you!  Today's blog augments my social media posts this week on chronic cough. I mean, now is definitely not the time to be dealing with chronic cough, am I right? With the coronavirus pandemic having us all just a bit twitchy about every scratchy throat, runny nose and cough, dealing with chronic cough can be even more stressful (which ironically can make your cough worse!). So today we're going to talk about the role of reflux - and more specifically "silent reflux," in the role of chronic cough. What is Silent Reflux? The medical term used is laryngopharyngeal reflux (say that 3 times fast!) or LPR. It occurs when the stomach contents flow back up in the the larynx and pharynx (so the back of the throat and mouth). The symptoms are different than traditional GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease - which is heartburn and regurgitation); LPR symptoms usually involve symptoms in the throat - cough, sore throat, voice issues like hoarseness and difficulty talking loudly and the sensation that something is in the throat (usually lots of throat clearing). Treating LPR/Silent Reflux Many patients who come to me for treatment of chronic cough are on, or have been on anti-reflux medications - usually proton-pump inhibitors (PPI's) like Prevacid, Protonix or Dexilant. However, studies show that PPI's are ineffective at treating LPR, and indeed, are ineffective at treating chronic cough. PPI's are meant for treating GERD, not LPR which is why they don't seem to have an effect. And cough is more associated with LPR than GERD. My first choices in dealing with suspected LPR are diet and diaphragm strengthening. Diet: Often it is acidic and spicy foods that will contribute to worsening symptoms of LPR. I usually give people a list of foods (like this one) that highlight those associated with increased reflux, have them check it and compare it to their usual diet. If they tend to eat a lot of the "reflux causing" foods, I will ask them to reduce those foods for a couple of weeks. If their cough symptoms improve, then we can start suspecting diet/LPR as a factor and figure out a plan from there. If there has been no change in symptoms, then we continue to look for other causes. Diaphragm: the Lower Esophageal Sphincter (basically the gate keeper between the stomach and the esophagus) is located within the diaphragm muscle. Its job is to keep stomach contents from coming back up the esophagus. Studies have shown that dysfunction of this sphincter can lead to LPR. Studies have also shown that the diaphragm can directly impact this. Strengthening the diaphragm via inspiratory muscle training has shown to reduce LPR. Inspiratory muscle training can also have a positive impact on the muscle function of the upper airway (larynx), which can also be beneficial for chronic cough. If you want a bit more science on LPR and treatments, I encourage to read this helpful review. This blog is by no means comprehensive for treating LPR, nor chronic cough, but merely addr I spoke with David Bidler from the Distance Project and Breathe to Perform about all things breathing and the impact of COVID-19 on our appreciation of health. We recorded the session and it's available to view on YouTube. Check it out!

It’s the start of a new year — a new decade. It’s often a time of renewed energy and resolutions. Exercise and lifestyle changes are at the top of many of those lists. Most of us know that “exercise is medicine”. Yet somehow it is so hard to regularly take that medicine. Habits, mindset, time and so many other facts of life can hamper momentum forward. Add to the mix chronic disease, acute illness or injury and the path towards your goals seems even more complex. It can be hard to know where to start and what works for you and your unique health scenario. Have you ever heard of health coaching? Health coaching is a style of treatment and therapeutic communication that helps patients gain the knowledge, skills, tools and confidence to become active participants in their care, so that they can reach their self-identified health goals. Self-management supports an active role for patients with chronic conditions by enabling patients to learn to manage their symptoms, maintain independence, and achieve a better quality of life. Health coaching has been shown to improve patients’ physical and mental health. Health coaching with a physiotherapist will see you have focused discussions on what matters most to you, what motivates you and why you are seeking change. As the patient you bring the expertise in “you". As physiotherapists we bring the expertise in cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neurological conditions, in therapeutic exercise, in strength and conditioning, and in behaviour and habit change. Here at Breathe Well Physiotherapy, we have particular expertise in all things breathing. We are here to guide you towards the goals that you have identified. And if your goals are still a bit fuzzy, we are here to help you refine that vision. Health coaching is a process in change. Chronic conditions, like COPD, lung disease, arthritis and many others, are not going to be “cured” so the focus shifts to influencing the factors that can be modified. Exercise, lifestyle, mindset, beliefs and understanding about our health can have powerful impacts on improving physical and mental wellness. Sustainable change does not happen overnight and often has many hiccups along the way. When a strong therapeutic relationship is at the core, you are more likely to learn how to overcome those hiccups and continue forward towards what matters most to you. At Breathe Well Physiotherapy, we believe that empowering our patients to breathe well, move well and live well is the most meaningful work we can do.  Time for another installment of "What's breathing got to do with it?" This time we are talking about sleep, because, as it turns out, breathing and sleep are pretty intricately related. Today we will look at a few ways that poor breathing patterns might be impacting your quality of sleep. Getting to sleep Do you climb into bed each night, only to lie there staring at the ceiling, wondering when sleep will come? A lot of patients that I see report having difficulty falling asleep. These patients also tend to have a more stimulating breathing pattern: rapid and dominated by upper chest movement. This type of breathing tends to keep the body in a hyper-aroused state - it's ready for anything, anytime. Indeed, research has shown that patients with insomnia have increased brain activity, abnormal hormone secretion, elevated heart rate and sympathetic nervous system arousal when they do sleep. It's as if their bodies don't know how to turn off. This is where breathing retraining comes in. Learning how to engage in a slower, more effortless breathing pattern, can help to activate our parasympathetic nervous system. This the "rest and digest" part of our autonomic (automatic) nervous system, and helps to put the brakes on the flight or fight side. Those of us who try to cram as many things into the day as possible, running from one activity to the next, dealing with stressful work situations, spouses, kids, etc may not remember what it feels like to turn off, tune out and relax. Learning how to let go as well as using mindfulness to help deactivate the stress response is key to getting the body better prepared for transitioning to sleep. I've had many clients report that they ended up falling asleep practicing finding calm- and that wasn't even the intended goal! Breathing During Sleep During normal sleep stages, several changes occur to our breathing. As we transition into sleep, there is a decrease in signals to the muscles of the chest and upper airways. This results in increased resistance in the upper airways and less activation of the chest muscles. During the next transition into REM sleep, all of the skeletal muscles of the body become atonic - meaning they relax nearly completely. The theory behind this being that we do not then act out our dreams. During this time, breathing is critically dependent on the function of the diaphragm, as it will often have an increase in activity. For most individuals, these changes to breathing patterns at night do not pose a problem. However, for anyone that has altered breathing patterns due to diaphragm weakness, this can lead to sleep disorders. Diaphragm weakness is seen in a number of situations:

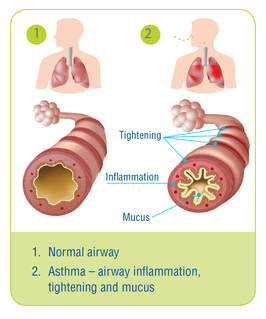

Treatment for Sleep Disordered Breathing The gold standard for addressing sleep apnea is continuous positive airway pressure - or CPAP. Essentially a machine will deliver a constant stream of air through the mouth or nose at night to ensure that the airways do not collapse and cause a stoppage in breathing. In addition, lifestyle changes such as weight loss and sleep hygiene are encouraged. What is also showing some promise in the treatment of sleep apnea, is inspiratory muscle training (IMT). IMT strengthens the diaphragm, and studies are showing that IMT can decrease snoring, improve sleep quality and decrease blood pressure issues related to sleep apnea. IMT is non-invasive, inexpensive and relatively easy to perform and should be considered to help treat sleep apnea. In addition to strengthening the diaphragm, there has also been some interesting results using didgeridoo playing as a way to tone the muscles of the upper airways. One ear, nose and throat doctor in the UK advocates the use of these exercises to help tone the throat muscles to help reduce snoring. Another study suggests that singing might just do the same! If you are concerned about your sleep quality, feel free to drop us a line to discuss what kind of treatment options we have here at Breathe Well Physio. We can help you turn off the fight or flight response to help you transition to sleep if you struggle to fall asleep. We can also get you started with an IMT program to strengthen your diaphragm to get you through all sleep phases. And if the problem is your upper airway function, we even offer voice exercises from a professional voice teacher to help tone those muscles to reduce snoring and sleep disruptions!  Image from www.lung.ca Image from www.lung.ca Well I suppose that seems like an obvious title. Of course breathing has everything to do with asthma, but today we are going to look at it from a slightly different perspective. We'll think outside the lung so to speak, although first we need to just quickly review what asthma is and why it makes breathing difficult. What is Asthma? Asthma is classified as a chronic disease that affects the airways or breathing tubes. With asthma, the airways tend to be more sensitive to things like air pollution, cold, viruses and sometimes exercise. Airways become inflamed and swollen, and the muscles around them also contract, making it harder to breathe - think of trying to drink a thick milkshake through a very tiny straw instead of a fat one. Symptoms of asthma include shortness of breath, wheezing (noisy breathing), coughing and tightness in the chest. When triggered, the increased struggle to breathe can lead to feelings of anxiety and panic - which makes sense, since for our brain, breathing is the number one thing it tries to preserve on a daily basis. Why Think Outside the Lung? So the good news about asthma, is that it responds quite well to medications and therfore is labelled as "reversible." This does not mean that medications cure asthma, simply that they can help control the inflammation and make breathing easier. However for some people, despite having optimal medication therapy, symptoms of breathlessness persist. And in these instances, we need to think outside the lung to understand why. When breathing is difficult - whether due to asthma, or maybe heavy exercise or sometimes even from a really bad cold - our body calls upon our helper, or accessory, muscles of breathing. These muscles are located in the chest, neck and shoulder region and help to lift up the ribs and breastbone to allow for more enter the lungs. At this point, we may also switch to mouth breathing as it offers up less resistance to breathing. You can try this on yourself to see: put one hand on your chest and one on your belly and breathe normally through your nose. Now open your mouth and take a slightly bigger breath. You will notice that your breathing has less resistance and your chest moves more than with your mouth closed. When breathing is more laboured, this mouth-chest breathing pattern is a good response to have. The problem arises when this emergency response breathing pattern becomes the new normal. This can happen in people with asthma. Studies (see references below) have shown that breathing dysfunction is common in persons with asthma, and that sub-optimal breathing patterns are associated with decreased perceived asthma control. The reasons behind changing breathing patterns are many, but the important point is that most dysfunctional breathing patterns are learned. Here is an example of how the body learns: let's say Mary has asthma. When Mary's asthma is triggered, she feels anxious and short of breath. When she takes her medication, her symptoms are relieved. However, Mary goes to work, she has a manager that she doesn't get along with. Often, interactions with her manager leave Mary feeling quite anxious and short of breath. When she feels this way, Mary takes her asthma medication because she feels like it could be her asthma. Only the medications don't seem to help. She returns to her doctor for more testing because her asthma symptoms are worsening. The testing shows her lungs are not any worse, despite her increase in breathlessness. This is a common scenario in my practice. What has happened is that Mary's stress and anxiety from work triggers a similar response to asthma. Poor breathing patterns can often mimic asthma symptoms, yet because the problem is not airway inflammation, medications don't often help. Sometimes, being anxious and changing your breathing pattern (generally, anxiety causes a faster, shallow breathing pattern) may actually trigger asthma too, so it can become a bit confusing. How Physiotherapy Can Help So what is someone like Mary to do, if the testing shows her lungs are not any worse, yet her symptoms are? Accessing treatment by a physiotherapist trained in treating breathing disorders may be a step in the right direction. Here at Breathe Well Physio, we become "breathing detectives" to find out what is causing the symptoms. We look at breathing patterns and breathing chemistry, we factor in things like stress, anxiety and sleep and we also look at how you move (you'd be surprised at how many people come through our doors that hold their breath every time they move!). There is plenty of evidence to support the use of breathing retraining as a way to improve asthma control (again, see the references listed below). Learning optimal breathing strategies and incorporating them into everyday functional activities is essential in helping to control asthma. For Mary, a big component would be recognizing the difference between asthma and stress-related breathing dysfuntion. We may not be able to do anything about Mary's manager, but we can teach Mary to recognize her physical symptoms and use strategies to help settle them. I must point out at this point, breathing retraining is not meant as a "cure" for asthma - and I would advise anyone with asthma to be very wary of any product or method that claims to cure asthma. Breathing retraining is an adjunct to medical therapy and is not a replacement. It is also very important, given that statistics show nearly 30% of asthma diagnoses are actually misdiagnosed, that if you have been told you have asthma, be sure this is confirmed with appropriate lung testing. Simply being out of breath when exposed to environmental allergens or exercise is not enough to confirm asthma. If you are wondering if you can get better control of your asthma or have concerns about your breathing, be sure to check in with us here at Breathe Well Physio and we would be happy to discuss it with you. Until next time...breathe well, move well ...BE WELL! References: Mike Thomas, R K McKinley, Elaine Freeman, Chris Foy. Prevalence of dysfunctional breathing in patients treated for asthma in primary care: cross sectional survey. BMJ VOLUME 322 5 MAY 2001 bmj.com Jane Upton et al. Correlation between Perceived Asthma Control and Thoraco-Abdominal Asynchrony in Primary Care Patients Diagnosed with Asthma. Journal of Asthma, 2012; 49(8): 822–829 Eirini Grammatopoulou et al. The Effect of Physiotherapy-Based Breathing Retraining on Asthma Control. Journal of Asthma, 48:593–601, 2011 Elizabeth A Holloway, Robert J West. Integrated breathing and relaxation training (the Papworth method) for adults with asthma in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax 2007;62:1039–1042. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.076430 |

AuthorI'm a physiotherapist who is passionate about educating anyone and everyone about the impact breathing has on our health. Archives

November 2020

Categories |